Courtesy - Wall Street Journel

Negotiations Resume, With Nod to Conservatives' Objections

WASHINGTON -- The Bush administration and Congress closed in on a new compromise aimed at stabilizing U.S. financial markets, a move designed to assuage conservatives who one day earlier had staged a revolt against the controversial $700 billion project.

The potential compromise isn't yet final, and details could change. But as of Friday night it appears that the plan's central elements, as originally envisioned by the Treasury Department, remain intact.

Congressional leaders were planning for possible votes Sunday.

The renewed effort represents a remarkable turnaround from the fracas that engulfed Washington Thursday night. In a sign of the political tensions at play, an earlier compromise plan was thrown into disarray after a White House meeting of top leaders -- including the two presidential candidates -- descended into a shouting match.

Republican nominee Sen. John McCain had returned to Washington to attend bailout negotiations. But the interjection of the presidential campaign, and the resulting finger-pointing, upset the delicate balance that had been struck in negotiations between congressional Democrats and Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson.

"I would hope the two presidentials would go to the debate tonight and leave us alone to get our work done here," said Sen. Harry Reid, a Nevada Democrat, sounding exhausted on the Senate floor Friday morning.

Under the Bush plan, the Treasury Department would be able to buy $700 billion of toxic investments currently burdening many financial institutions. The hope is that doing so would encourage investors to recapitalize the struggling banks, and get the nation's bond markets working again.

It would also, however, put taxpayers on the hook for potential losses if the investments bought by the government didn't later recover some of their value.

House Republicans, antsy about the power granted to the Treasury under that original plan, wanted to replace it with one based on an insurance model: Banks would pay premiums into a pool of money that would then be used to cover losses on the bad assets in question.

Treasury officials had earlier told lawmakers the concept was unworkable, people familiar with the matter said. Indeed, officials there briefly considered it, but concluded it wouldn't be as effective in clearing the rot from banks' balance sheets.

The compromise being hammered out Friday night would graft the insurance concept onto the original Treasury plan, most likely as an option. That would satisfy the administration, which could chose not to use it, as well as conservative lawmakers, who can claim to have influenced the legislation.

The White House has already agreed to other Democratic demands for the bailout, including greater oversight of the plan, and pay curbs for executives at some companies that benefit from the bailout.

The administration also agreed to a commitment to help struggling homeowners. And it agreed for the $700 billion to be released in installments; $250 billion would be made available immediately.

As Friday unfolded, Democrats signaled a willingness to consider including some version of the insurance proposal. "Adding insurance as an option...that's never been an issue," said Rep. Barney Frank (D., Mass.), chairman of the House Financial Services Committee and a lead negotiator.

At a late-afternoon news conference, House Speaker Nancy Pelosi sounded conciliatory, suggesting that Mr. Paulson should have "the latitude to accept any and all proposals," so long as they don't interfere with the core goals of the bailout plan.

The unexpected opposition from House Republicans on Thursday had thrown into chaos efforts to craft a rescue package for the financial markets. Democratic leaders of the House and Senate, after working with the Bush White House for several days on details, said they felt blindsided by the Republican move.

The face-off reflected years of tension between the Bush White House and House Republicans, and exposed the ideological differences within the Republican Party over the role of government in free markets.

President George W. Bush, who urged lawmakers to "rise to the occasion" Friday, has said his first instinct is to not intervene in the market. But he became convinced of the need after Mr. Paulson and Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke warned that the financial crisis could spread to Main Street from Wall Street and throw the country into a deep recession.

Many Senate Republicans, including Bob Bennett of Utah and Judd Gregg of New Hampshire, have tried to be supportive of the White House's efforts to find common ground with Democrats. But conservatives who dominate the Republican Party's caucus in the House have been less amenable, particularly those disaffected with the Bush administration's sizable domestic spending and the realities of life as a minority party.

Rep. Tom Davis (R., Va.) said Republicans have felt like "bystanders" the past two years and wanted to be brought into the negotiations as full partners. Democrats "have got to come and meet us halfway," he said.

By midweek, it became clear that only a couple dozen of the 199 House Republicans were likely to support the plan in its existing form.

House Republicans say their alternative proposal would bring stability and new capital to the market. It would also remove regulatory barriers that they say block private investors from investing capital into ailing financial institutions.

"We were simply trying to come up with a constructive solution to break an impasse," said Rep. Paul Ryan (R., Wis.), who outlined the plan to Sen. McCain in a meeting Thursday.

The struggle over the bailout bill represents one of the most dramatic congressional showdowns of recent years. In 1990, the Democratic House voted down a major deficit-reduction package backed by the administration of the first President Bush. The package was later brought back to the floor and approved, but only after changes that tilted the measure to the left.

A few years later, the Republican-controlled Congress balked at the Clinton administration's plans to help rescue Mexico's economy, forcing the administration to use other measures to achieve its goals.

At a closed-door meeting of House Republicans on Friday, House Minority Leader John Boehner and other party leaders received an ovation for having resisted pressure to support the Bush-backed package during a White House meeting the previous day.

skip to main |

skip to sidebar

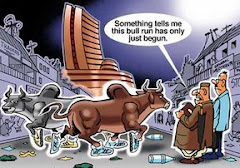

When the bulls win, the markets go up...

The stock markets are the heart of the corporate world. The stock markets are where companies and business reputations are made and unmade. This site is a guide for information, news and views. There is no expertise here - simply status reports and links to specialised sites where further information is available. The stock markets help me update my knowledge of corporate India. Keeping track of businesses is the main purpose of this site. This site is not a guide for investment decisions.

Facebook Badge

Hello from Mumbai...

Labels

- '4.4 mn jobs lost (1)

- 'THE NATIONAL' ABU DHABI AND 'THE TRIBUNE' NORTH INDIA (1)

- "CITY AUTHOR PENS RECORD" - SHARING THE NEWS ITEM WHICH WAS PUBLISHED IN YESTERDAY'S 'DAINIK JAGRAN' NEWSPAPER ('CITY PLUS' SUPPLEMENT) (1)

- 000 (1)

- 000 cr (1)

- 000 cr in 100 days (1)

- 000 cr in August (1)

- 185 cr in stocks so far this year (1)

- 2013 (1)

- 2015 (2)

- 296 cr (1)

- 435 level (1)

- 52 new trains announced in India's rail budget (1)

- 775 points (1)

- 835 (1)

- A positive and individual friendly budget (1)

- a record book published by Coca Cola India (1)

- Abhinav Bindra bags first Olympic gold for India at Beijing - and first ever Indian invdividual gold medal... (1)

- Advice from Warren Buffet (1)

- An article about my five books...published in eight months... (1)

- and first political crime thriller) (1)

- Another newspaper story about my career as an author (1)

- Article about me: "Writing a new chapter at 50 plus"... (1)

- Article about my books and me in the national daily The Hindustan Times (1)

- ARTICLE ABOUT MY FIVE BOOKS IN THE TIMES OF INDIA (1)

- ARTICLES ABOUT MY BOOKS IN 'GULF NEWS' DUBAI (1)

- as author with most books on crime fiction in shortest time (1)

- Asia stocks fall for 4th day; European shares down (1)

- Asian markets lower as global rally loses steam (1)

- Asian stocks posted their worst weekly performance in nearly two months (1)

- AT THE TIMES GROUP BOOKS STALL...DELHI WORLD BOOK FAIR 2013...WITH TWO OF MY BOOKS (1)

- Bailout Compromise Gets New Life (1)

- banking stocks slide (1)

- Biggest single day gains (1)

- Biggest single day gains of the sensex... (1)

- Blood Donor Day (1)

- BPO (1)

- BSE Sensex at 4-½-month closing low; banks drop (1)

- BSE Sensex closes up 1.2 pct (1)

- BSE Sensex extends gains to 2 pct (1)

- BSE Sensex posts best weekly gain in 10 months (1)

- BSE Sensex seen rising 20% by end-2011: Poll (1)

- BSE Sensex slips 3rd day; telcos slide (1)

- Bulls fight back (1)

- closes at 17 (1)

- Companies look at CSR initiatives for branding in slump (1)

- Corporate results (1)

- Deficits falling in India (1)

- Despite fewer cuts (1)

- DLF slip (1)

- Economists see U.S. recovery weakening - survey (1)

- Eight book reviews of my new novel "Chief Minister's Mistress"..... (1)

- emerging economies: IMF (1)

- energy (1)

- energy and metals rally (1)

- Europe taking good steps - IMF chief (1)

- Featuring for two consecutive years in the Limca Book of Records (2012 and 2013) (1)

- Feb manufacturing growth at 20-month high - PMI (1)

- FII action (1)

- FII inflows to cross $10 bn-mark in Sept. 2009 (1)

- FIIs bullish on India (1)

- FIIs pour Rs 51 (1)

- Fresh Tumult as Signs of Recession Go Global (1)

- G-20 leaders reach historic pact on global recovery (1)

- G-20 Summit Offers Mostly Promises (1)

- Garments maker Provogue India to buy back shares worth Rs. 50 crore at Rs.100 a piece (1)

- GLOBAL ECONOMY 2010 - Crystal ball gazing (1)

- Global leaders seek Indian PM's expertise to salvage financial crisis (1)

- Gold hovers near record highs as economic fears persist (1)

- GOOD CHEER ON APRIL 13 (1)

- Handcuffed IMF chief charged in sex assault case (1)

- Happy Independence Day... (1)

- How the major indices fared in 2007 (1)

- I feature in the Forbes 2014 list of Top 100 Celebrity Indian Authors (1)

- I have just returned from a week's stay in Alpbach (1)

- IDBI Bank aims to enhance base in SME (1)

- IIP Industrial growth at 6.8% in July (1)

- IIP nos fail to boost Sensex; Ranbaxy (1)

- In a striking shift (1)

- India celebrates 63 years of Independence (1)

- India celebrates its 63rd Independence Day on August 15th... (1)

- India Inc prunes Q4 losses by 28.5% (1)

- India Inc resumes hiring drive amid recovery signals (1)

- India to outperform rest of Asia (1)

- India world's best performing stock market (1)

- Indian cos in Forbes 'Best Under A Billion' list (1)

- Indian economy to grow by 8.5%: CII (1)

- Indices (35)

- Industrial Production grows (1)

- Industry expands 7 per cent in July (1)

- Industry recovers as excise up 22.7% in August 2009 (1)

- Infosys profit falls 0.9 pct but outlook improves (1)

- Infosys Q1 net falls 2.6 pct (1)

- Infosys Q2 net profit up 13 pct (1)

- Instant view: Budget proposals (1)

- Interview in Spectral Hues.....September (1)

- Investors enter 2011 in bullish mood - Reuters poll (1)

- ITeS industry could grow to $225 billion by 2020 (1)

- Japan Stocks Rise; Nikkei Posts Biggest 3-Day Rally in 38 Years (1)

- Japan's economy rebounds in 2Q on export growth (1)

- JPMorgan Chase posts better-than-expected profit (1)

- Kingfisher sacks 300 ex-Air Deccan employees (1)

- lags forecast (1)

- long way before economy revives' (1)

- Major gainers and major losers (11)

- MAJOR INDEXES CLOSING SNAPSHOT - April 18th... (1)

- Market closings on Friday (1)

- Market commentary (93)

- Market trends (2)

- Markets around the world (14)

- metal (1)

- Moody's revises India growth forecast upwards to 6.4 percent (1)

- Most India funds outpace Sensex since March 9 (1)

- MOUNTAIN OF DEBT: Rising US government debt may be next (world) crisis (1)

- My Author's Corner event at the Delhi World Book Fair (1)

- My first book... (1)

- MY FIRST FOUR BOOKS ON A T-SHIRT .... (1)

- My interview in 'Suburb'.....September (1)

- My new book (my 16th release (1)

- My second novel: "The Inheritance" has been published (1)

- My three books (1)

- MY WEBSITE (1)

- National Record Certificate: 2014.....Fastest published crime fiction author of India (fourth year in a row) (1)

- New Horror Serial On Television... (1)

- News (34)

- News and observations (1)

- News briefs (1)

- News in brief - US (1)

- No fare hikes (1)

- PepsiCo announces $500 million investment in India (1)

- POLL - MFs see stocks rising; eye financials (1)

- POLL - Sensex set for slower rise in 2010 (1)

- Public sector oil firms slash ATF price (1)

- Record gains for Sensex in 17 years (1)

- retail sectors (1)

- Riding the bull charge (1)

- RIL consolidated FY09 net at Rs 15 (1)

- Risk back in vogue for investors abroad (1)

- Rs 1 lakh cr club shrinks (1)

- Rules for Investing in the Next Bull Market (1)

- Sara Lee selling stake in Godrej Sara Lee JV (1)

- Satyam saga shows holes in India corporate governance (1)

- says LIC investment chief (1)

- SBI says economy likely to need more help (1)

- See Sensex at 25K levels by 2007 end (1)

- Senate prospects uncertain (1)

- Senate Vote Gives Bailout Plan New Life (1)

- Sensex creates history: hits 14 (1)

- Sensex down by 6.36% in the week (1)

- Sensex ends 2007 with gain of 47% (1)

- Sensex ends up 744pts (1)

- Sensex falls again - by over 250 points (1)

- Sensex gains 250pts (1)

- Sensex has longest winning streak since August 2005 (1)

- Sensex loses 265 pts (1)

- SENSEX SECONDS PEOPLE'S VERDICT... ZOOMS 17% (1)

- Sensex shed 445pts; Realty (1)

- Sensex surges 5%; banking (1)

- Sensex to touch 19.5k by 2010 - 2011 fiscal end (1)

- Sensex up second week in a row on fund buying (1)

- Sensex zooms up 484 points; biggest single day gain in six months (1)

- September 12... (1)

- September sonnet for stocks: A sliding Sensex? (1)

- Seven of top-10 firms gain Rs 51 (1)

- Share pledge disclosures weigh on blue-chip stocks (1)

- small investors flee US stock markets (1)

- Stock Market Rebound Boosts Warren Buffet's Berkshire (1)

- Stocks rise after G-20 say stimulus will stay (1)

- Survey: most economists see recession end in '09 (1)

- Tata leads wealth creation in 2009 (1)

- The biggest winners and losers of 2007 on the sensex (1)

- The blind investment banker with a vision (1)

- The first buyer of my second book - Shivangi Dhingra (1)

- The frugal billionaire...and world's richest man (1)

- The other India growth story: rising donations (1)

- The world's richest person (1)

- Tight Credit Compound US Housing Woes (1)

- TIMES OF INDIA - "SPEED WRITER IN RECORD BOOKS" (ARTICLE IN YESTERDAY'S NEWSPAPER ABOUT MY BOOKS AND MY RECORD ENTRY IN THE LIMCA BOOK OF RECORDS) (1)

- Top 8 cos add Rs 23 (1)

- triggers trade halt (1)

- TWO RECENT NEWSPAPER REPORTS ABOUT MY WRITING CAREER (1)

- U.S. Outperforms Overseas Markets (1)

- U.S. Seals Bailout Deal (1)

- up stake in more companies (1)

- UPA-II effect: FIIs infuse Rs 23 (1)

- US Congress approves stimulus package (1)

- US economy (9)

- US House passes auto bailout (1)

- US markets (22)

- US May jobless rate seen rising... (1)

- US Recession (1)

- Wall Street set for a mixed opening (1)

- What the Past Teaches (1)

- Wishing everybody a very happy Holi. Enjoy the festival of colours. May your lives be always filled with beautiful colours and lots of laughter... (1)

- Wishing you a very happy Holi (1)

- Wkly review: Sensex ends up 48pts (1)

- Wkly Tech Analysis: Watch out for the 8 (1)

- Wkly Tech: Nifty slide to accelerate below 2 (1)

- World stocks set for best Dec performance in a decade (1)

- Worst seems to be over for India Inc: Ficci survey (1)

- WRITE UP IN THE 'LIMCA BOOK OF RECORDS' 2012 EDITION (1)

- Yesterday was Priti and my nineteenth wedding anniversary (1)

India celebrates 60 years of Independence...

Stock Market Terminology...

Stock market terms you must know (this article is for new entrants to the dizzy world of stocks and stock market trading):

As a stock market investor, you will regularly come across words like Sensex, Nifty, correction, rally et al...

Also, as a regular reader of business newspapers you will come across these and a host of other terms that describe the stock market activities.

You will also come across research reports from brokerage houses that talk of buying, selling and holding of a company's share.

Let us go through a few of these terms used in routine stock market parlance.

Sensex

It is an index that represents the direction of the companies that are traded on the Bombay Stock Exchange, BSE. The word Sensex comes from sensitive index.

The Sensex captures the increase or decrease in prices of stocks of companies that it comprises. A number represents this movement. Currently, all the 30 stocks that make up the Sensex have reached a value of 14,355 points.

These companies represent the myriad sectors of the Indian economy. A few of these companies and the sector they represent are: ACC (cement), Bajaj Auto, Tata Motors, Maruti (automobile), Infosys, Wipro, TCS (information technology), ONGC, Reliance (oil & gas), ITC, HUL (fast moving consumer goods) etc.

Each company has a weight assigned to it. Companies like Reliance, Infosys, and HLL have higher weightages compared to others like HDFC, Wipro, or a BHEL.

The increase or decrease in this index, the Sensex, is the effect of a corresponding increase or decrease in the stock market price of these 30 companies.

Nifty

It is the Sensex's counterpart on the National Stock Exchange, NSE.

The only difference between the two indices (the Sensex and Nifty) is that the Nifty comprises of 50 companies and hence is more broad-based than the Sensex.

Having said that one must remember that the Sensex is the benchmark that represents Indian equity markets globally.

The Nifty 50 or the S&P CNX Nifty as the index is officially called has all the 30 Sensex stocks.

The NSE Nifty functions exactly like (explained above) the BSE Sensex.

Bull

A particular kind of investor who purchases shares in the expectation that the market price of that company's share will increase.

S/he sells her/his stock at a higher price and pockets the profit. Simply put, the bulls buy at a lower price and sell at a higher price.

For instance, if a bull buys a company's share at Rs 100, s/he would prefer selling the same stock at Rs 120 or any price higher than Rs 100 to make a profit.

Usually, a bull buys first at a lower price and sells later at a price higher than her/his cost of purchase.

Bulls are happy when the markets (the Sensex and Nifty) move upwards. A falling market takes bulls into hibernation.

Bear

Bull's counterpart is the bear.

A bear sells stocks first that s/he owns or borrows from, say a friend, and then purchases the same quantity of shares at a lower price.

If a bear sells first, say 100 shares of Ranbaxy at Rs 400, and later purchases the same number of shares at Rs 375, then her/his profit is Rs 25 (400-375) per share.

This way s/he has got back the 100 shares of Ranbaxy and simultaneously made a profit of Rs 2500. The shares can later be returned to the bear's friend if s/he had borrowed the same from a friend.

There are bears in the market that sell shares first without actually owning them unlike in the above example. Such selling is called naked short selling or going short on a stock.

Bears are happy in a falling market.

While individual investors can engage in selling first and buying later (also referred to as short selling), mutual funds and foreign institutional investors are not allowed this luxury in India yet.

Squaring off

A process whereby investors/traders buy or sell shares and later reverse their trade to complete a transaction is called squaring off of a trade.

Indian equity markets remain open between 9:55 am and 3:30 pm normally (At times there are sun outages when satellites fail to link with ground infrastructure of the two exchanges (the servers where buy and sell orders are matched). During these times the trading period is extended till 4:15 pm to compensate for the time lost in between).

If you purchase 50 shares of say Infosys and sell them later before the market closes then you have squared off your buy position.

Similarly, if you sell 100 shares of Maruti and purchase them later then you have squared off your sell position.

Equity market rules in Indian allow investors/traders to engage in day trading.

Day trading is a mechanism whereby investors/traders can buy, say 100 shares of a company as soon as the BSE, NSE opens (the working hours are 9:55 am to 3:30 pm in normal times) and sell the same amount of shares later (bulls) before the two stock exchanges close. However, a stock bought on the BSE cannot be sold on the NSE and vice-versa.

Similarly investors/traders can also sell first and buy later (bears) during the course of the day to square off their sell positions.

Rally

The word suggests the gain made by the Sensex or Nifty during the course of the day. If such gains are made on a regular basis then market participants like investors, brokers etc call it as a market rally.

If the Sensex moves from 14,000 points to 15,000 points in a span of say 14 or for that matter 20 trading sessions (the stock markets remain closed on Saturdays, Sundays and other bank holidays) then the phenomenon is referred to as a rally.

Bulls are always said to be active during a market rally.

Crash

As the word suggests, crash refers to a sudden and steep fall in the value of Sensex and Nifty.

Bears are said to be active and happy during the market crash as their style of trading (sell first and buy later) helps them make good money during a crash.

Correction

A correction (or a measured fall) in the Sensex and Nifty takes place when these indices rise for a few days and then retrace or shave off some of these gains.

Say if the markets rally from 13,000 to 14,000 points in 10 days and the again fall to 13,700 points in the next five-six days then this action is termed as a market correction.

It is like a woman/man resting for some time after running a long distance race. Like human beings the market too needs to take rest after a smart rally.

Market experts consider such corrections healthy because during this period the ownership of shares moves from weak hands (short-term investors) to strong hands (long-term investors). Corrections are generally considered as signs of strength after which the markets (the Sensex and Nifty) gets once again poised for a further rally.

Bonus shares

These are the free shares that a listed company gives its shareholders.

A bonus is declared after a discussion amongst the board members that make up the management of a company.

A bonus issue is looked upon as a way of rewarding shareholders.

For instance, let us take a company A that has made a profit of Rs 100 crore in the financial year 2007 (April 1, 2006 to March 31, 2007).

Out of this amount the company may need Rs 50 crore for say buying machinery or constructing a new warehouse. And the remaining Rs 50 crore the company puts into its reserve pool or idle cash that the company has no plans to spend.

It can then issue bonus shares out of these Rs 50 crore.

When a company declares a bonus issue it converts this idle cash into shares that are then distributed amongst its shareholders. This process is called capitalising of reserves.

A bonus is usually declared as a ratio. A bonus issue in the ratio of 1:1 means you will get one free share for every one share of the company you own.

A 2:1 bonus issue (or two for every one held) means you will get two free shares of a company for every one that you own. Similarly, a 5:1 bonus issue will give you five free shares for every one share that you own.

Dividend

It is again a way of rewarding a company's shareholders. A dividend is generally issued as a percentage of the face value of a share. Face value is the nominal price of a company's share.

A share can have different face values like Re 1, Rs 2, Rs 5, Rs 10 or Rs 100. An 80% dividend on a share of face value Rs 2 (Rs 1.6) will always be less than a dividend of 20% declared on share of face value Rs 10 (Rs 4).

Like bonus shares, dividend amount also comes from a company's free cash reserves.

Book closure date

This is the date on which a company closes its books for business after it announces a bonus or dividend. The company's registrar keeps a track of who owns how many shares of that particular company.

Any investor having shares in his/her demat account before this date becomes eligible for the bonus issue or the dividend declared.

Say a company A announces a 1:1 bonus issue and the book closure date is February 28, 2007. If you don't own this company's share and want to avail of the bonus offer then you must not only buy this share before February 28 but also make sure that the number of shares purchased by you are transferred to your account from the seller before this date.

If the ownership of shares is reflected in your account after February 28 then you will not get any bonus shares. The same is also true for dividend announcements.

This just sums up a few (but regularly applyed) terms used by stock market participants.

As a stock market investor, you will regularly come across words like Sensex, Nifty, correction, rally et al...

Also, as a regular reader of business newspapers you will come across these and a host of other terms that describe the stock market activities.

You will also come across research reports from brokerage houses that talk of buying, selling and holding of a company's share.

Let us go through a few of these terms used in routine stock market parlance.

Sensex

It is an index that represents the direction of the companies that are traded on the Bombay Stock Exchange, BSE. The word Sensex comes from sensitive index.

The Sensex captures the increase or decrease in prices of stocks of companies that it comprises. A number represents this movement. Currently, all the 30 stocks that make up the Sensex have reached a value of 14,355 points.

These companies represent the myriad sectors of the Indian economy. A few of these companies and the sector they represent are: ACC (cement), Bajaj Auto, Tata Motors, Maruti (automobile), Infosys, Wipro, TCS (information technology), ONGC, Reliance (oil & gas), ITC, HUL (fast moving consumer goods) etc.

Each company has a weight assigned to it. Companies like Reliance, Infosys, and HLL have higher weightages compared to others like HDFC, Wipro, or a BHEL.

The increase or decrease in this index, the Sensex, is the effect of a corresponding increase or decrease in the stock market price of these 30 companies.

Nifty

It is the Sensex's counterpart on the National Stock Exchange, NSE.

The only difference between the two indices (the Sensex and Nifty) is that the Nifty comprises of 50 companies and hence is more broad-based than the Sensex.

Having said that one must remember that the Sensex is the benchmark that represents Indian equity markets globally.

The Nifty 50 or the S&P CNX Nifty as the index is officially called has all the 30 Sensex stocks.

The NSE Nifty functions exactly like (explained above) the BSE Sensex.

Bull

A particular kind of investor who purchases shares in the expectation that the market price of that company's share will increase.

S/he sells her/his stock at a higher price and pockets the profit. Simply put, the bulls buy at a lower price and sell at a higher price.

For instance, if a bull buys a company's share at Rs 100, s/he would prefer selling the same stock at Rs 120 or any price higher than Rs 100 to make a profit.

Usually, a bull buys first at a lower price and sells later at a price higher than her/his cost of purchase.

Bulls are happy when the markets (the Sensex and Nifty) move upwards. A falling market takes bulls into hibernation.

Bear

Bull's counterpart is the bear.

A bear sells stocks first that s/he owns or borrows from, say a friend, and then purchases the same quantity of shares at a lower price.

If a bear sells first, say 100 shares of Ranbaxy at Rs 400, and later purchases the same number of shares at Rs 375, then her/his profit is Rs 25 (400-375) per share.

This way s/he has got back the 100 shares of Ranbaxy and simultaneously made a profit of Rs 2500. The shares can later be returned to the bear's friend if s/he had borrowed the same from a friend.

There are bears in the market that sell shares first without actually owning them unlike in the above example. Such selling is called naked short selling or going short on a stock.

Bears are happy in a falling market.

While individual investors can engage in selling first and buying later (also referred to as short selling), mutual funds and foreign institutional investors are not allowed this luxury in India yet.

Squaring off

A process whereby investors/traders buy or sell shares and later reverse their trade to complete a transaction is called squaring off of a trade.

Indian equity markets remain open between 9:55 am and 3:30 pm normally (At times there are sun outages when satellites fail to link with ground infrastructure of the two exchanges (the servers where buy and sell orders are matched). During these times the trading period is extended till 4:15 pm to compensate for the time lost in between).

If you purchase 50 shares of say Infosys and sell them later before the market closes then you have squared off your buy position.

Similarly, if you sell 100 shares of Maruti and purchase them later then you have squared off your sell position.

Equity market rules in Indian allow investors/traders to engage in day trading.

Day trading is a mechanism whereby investors/traders can buy, say 100 shares of a company as soon as the BSE, NSE opens (the working hours are 9:55 am to 3:30 pm in normal times) and sell the same amount of shares later (bulls) before the two stock exchanges close. However, a stock bought on the BSE cannot be sold on the NSE and vice-versa.

Similarly investors/traders can also sell first and buy later (bears) during the course of the day to square off their sell positions.

Rally

The word suggests the gain made by the Sensex or Nifty during the course of the day. If such gains are made on a regular basis then market participants like investors, brokers etc call it as a market rally.

If the Sensex moves from 14,000 points to 15,000 points in a span of say 14 or for that matter 20 trading sessions (the stock markets remain closed on Saturdays, Sundays and other bank holidays) then the phenomenon is referred to as a rally.

Bulls are always said to be active during a market rally.

Crash

As the word suggests, crash refers to a sudden and steep fall in the value of Sensex and Nifty.

Bears are said to be active and happy during the market crash as their style of trading (sell first and buy later) helps them make good money during a crash.

Correction

A correction (or a measured fall) in the Sensex and Nifty takes place when these indices rise for a few days and then retrace or shave off some of these gains.

Say if the markets rally from 13,000 to 14,000 points in 10 days and the again fall to 13,700 points in the next five-six days then this action is termed as a market correction.

It is like a woman/man resting for some time after running a long distance race. Like human beings the market too needs to take rest after a smart rally.

Market experts consider such corrections healthy because during this period the ownership of shares moves from weak hands (short-term investors) to strong hands (long-term investors). Corrections are generally considered as signs of strength after which the markets (the Sensex and Nifty) gets once again poised for a further rally.

Bonus shares

These are the free shares that a listed company gives its shareholders.

A bonus is declared after a discussion amongst the board members that make up the management of a company.

A bonus issue is looked upon as a way of rewarding shareholders.

For instance, let us take a company A that has made a profit of Rs 100 crore in the financial year 2007 (April 1, 2006 to March 31, 2007).

Out of this amount the company may need Rs 50 crore for say buying machinery or constructing a new warehouse. And the remaining Rs 50 crore the company puts into its reserve pool or idle cash that the company has no plans to spend.

It can then issue bonus shares out of these Rs 50 crore.

When a company declares a bonus issue it converts this idle cash into shares that are then distributed amongst its shareholders. This process is called capitalising of reserves.

A bonus is usually declared as a ratio. A bonus issue in the ratio of 1:1 means you will get one free share for every one share of the company you own.

A 2:1 bonus issue (or two for every one held) means you will get two free shares of a company for every one that you own. Similarly, a 5:1 bonus issue will give you five free shares for every one share that you own.

Dividend

It is again a way of rewarding a company's shareholders. A dividend is generally issued as a percentage of the face value of a share. Face value is the nominal price of a company's share.

A share can have different face values like Re 1, Rs 2, Rs 5, Rs 10 or Rs 100. An 80% dividend on a share of face value Rs 2 (Rs 1.6) will always be less than a dividend of 20% declared on share of face value Rs 10 (Rs 4).

Like bonus shares, dividend amount also comes from a company's free cash reserves.

Book closure date

This is the date on which a company closes its books for business after it announces a bonus or dividend. The company's registrar keeps a track of who owns how many shares of that particular company.

Any investor having shares in his/her demat account before this date becomes eligible for the bonus issue or the dividend declared.

Say a company A announces a 1:1 bonus issue and the book closure date is February 28, 2007. If you don't own this company's share and want to avail of the bonus offer then you must not only buy this share before February 28 but also make sure that the number of shares purchased by you are transferred to your account from the seller before this date.

If the ownership of shares is reflected in your account after February 28 then you will not get any bonus shares. The same is also true for dividend announcements.

This just sums up a few (but regularly applyed) terms used by stock market participants.

The bulls and the bears are constantly fighting it out in the stock market...

When the bulls win, the markets go up...

Useful links

Click on the following links for more information on stockmarkets, corporate announcements, market news / analysis and stock prices...

Website of the National Stock Exchange of India (NSE)

Website of the Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE)

NSE Indices highlights

BSE Indices highlights

BSE stock prices and price trends

Website of Television Eighteen (Moneycontrol)

Website of Sharekhan

Website of The Economic Times

Website of The Financial Express

Website of Business Standard

Website of BUSINESSWEEK (Asia)

Website of Financial Times (Asia)

Website of Yahoo Finance

Website of DALLALSTREET

Website of Capital Market

Forthcoming Board Meetings

Blog Archive

-

▼

2008

(130)

-

▼

September

(12)

- U.S. Seals Bailout Deal

- Bailout Compromise Gets New Life

- Global leaders seek Indian PM's expertise to salva...

- Sensex shed 445pts; Realty, metal, banking stocks ...

- Kingfisher sacks 300 ex-Air Deccan employees

- PepsiCo announces $500 million investment in India

- Rs 1 lakh cr club shrinks

- Wkly Review: Sensex recovers sharp losses, ends we...

- News...

- Market closings on Friday, September 12...

- Industry expands 7 per cent in July

- Sensex ends up 551pts; banking, realty stocks rally

-

▼

September

(12)

My other blogs

If you would like to check out my other blogs, please click on the following links...

About Me

- Joygopal Podder

- I head fundraising in India for a leading international anti poverty development agency. Prior to this assignment, I worked for a leading child welfare organisation. Prior to this, I worked for an NGO looking after the elderly (type Joygopal Podder on Google search and you can view newspaper reports of various activites I have organised for the causes I work for). I moved to the "not-for-profit" sector after 15 years in industry. I am a freelance writer (my stories are used in text books of schools like Delhi Public School) and a Gold Medalist Law Graduate. I have a lovely family consisting of two talented and beautiful daughters and an interior designer-turned-marketing professional wife. I was born in London, worked for some time in the Middle East and now work in Delhi and live in the suburbs. I travel 15 days a month in India and abroad - and watch movies every weekend. I am maintaining the following blogs: http://compiledbyjoygopalpodder.blogspot.com http://mysteriesaroundus.blogspot.com http://noticeboardonanythingand everything.blogspot.com http://storiesbyjoygopalpodder.blogspot.com http://grandmothertales.blogspot.com http://stockmarketswithjoygopalpodder.blogspot.com

My family and me...

At work...

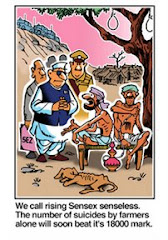

Cartoons by Ajit Ninan published in "The Times of India"...

India shining...

Bull run...

Rising sensex...

Effects of inflation...

Both sides of the coin...